Mozambique is a country of many opportunities thanks to its natural gas reserve with several of the largest African liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects at its northern shores.

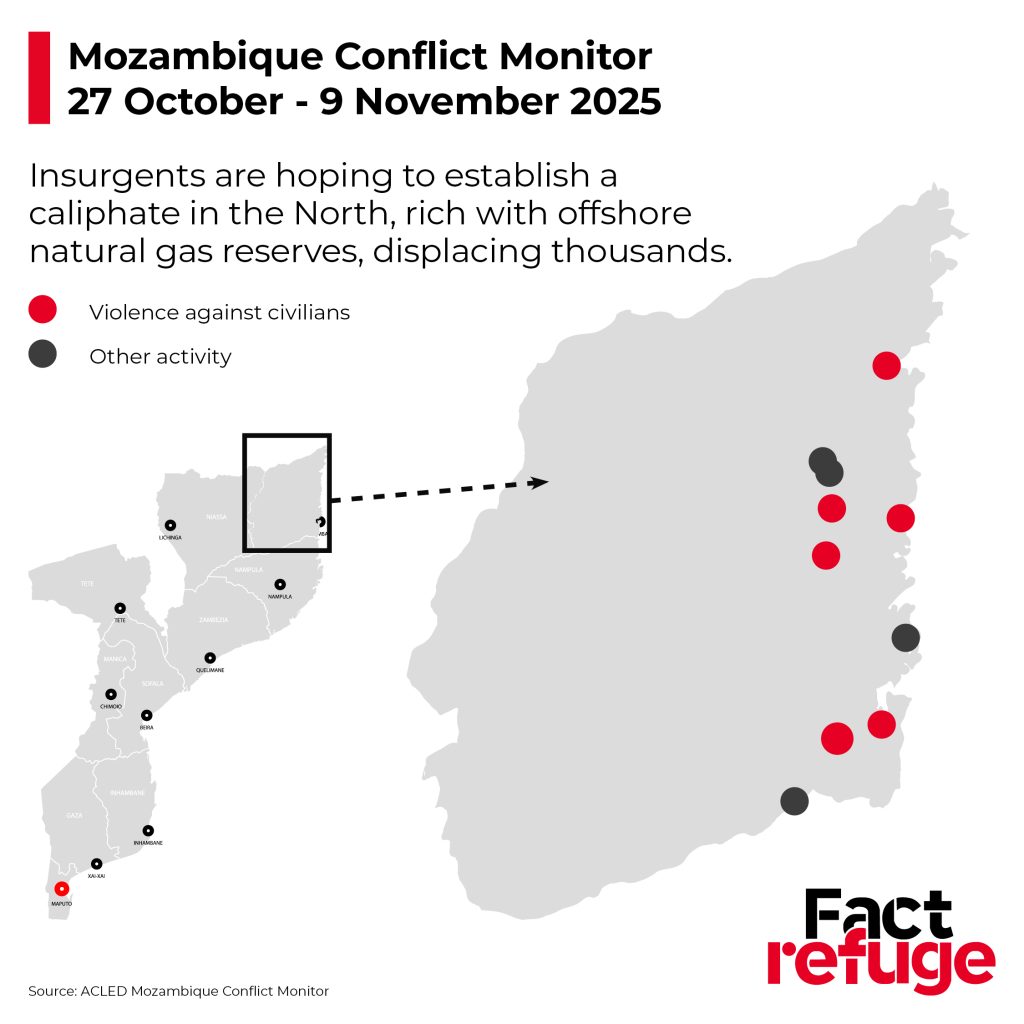

Despite this, the country relied on foreign aid to deal with the fallout of local Islamist conflicts that began in 2017, led by armed groups locally known as al-Shabaab, which have worsened recently, especially in the Cabo Delgado region.

According to an October report by UNHCR, more than 1.3 million people have been displaced, as, for the first time since the conflicts began, all 17 districts of Cabo Delgado have been directly affected.

As the humanitarian crisis deepens with the lack of international aid, energy giants halt their production, leaving the country with no money of its own.

Poverty and Conflict

Mozambique has the second-highest poverty rate, according to the initial estimates of the Human Development Index (HDI). The World Food Program (WFP) estimates that 82% of the population living on less than US$3 per day.

According to the World Bank’s assessment, GDP contracted 2.4% year-on-year in the first half of 2025 due to declines in industry and services, like the gas business.

Cabo Delgado is in an especially vulnerable situation; it has massive natural gas reserves, making it instrumental in the energy industry, but as insurgents have moved in, conflict has forced a stop to operations.

Insurgents, claiming to be part of the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) affiliated with ISIL, announced in 2020 that they fight to establish an “Islamist caliphate” in the north.

Between 20 July and 3 August, 57,034 people fled the escalating attacks in the province in only two weeks.

According to Save the Children, more than 30,000 were children, separated from their families. More recently, in September, nearly 22,000 fled in a single week.

Since insurgent attacks target civilians, reports of killings, abductions, and sexual violence reach the locals, too. Many times, people flee before attacks occur out of fear. Women are especially vulnerable when they collect firewood or water, while children are forced into recruitment.

Reports by the United Nations suggest the situation is worsening, with civilian targeting doubling compared to last year, reaching 633 incidents between January and October 2025.

ACLED’s (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data) Conflict Monitor for Mozambique reports 6,316 fatalities from political violence, with 2,670 civilian casualties, since the conflict began on 1 October 2017 up until 12 November 2025 in Cabo Delgado alone.

Humanitarian Assistance Dependence

The region is dependent on global humanitarian aid to maintain necessities like food provisions and healthcare centers.

The WHO-led teams report that around 60% of facilities in the worst-affected districts are non-functional due to staff displacement and looting. In the northern city of Mocímboa da Praia, the only hospital is operating with less than 10% of its staff.

The lack of personnel is a major issue: with the rainy season beginning, rampant cholera and malaria cases are expected to spike. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported nearly 4,500 new cholera cases between October 2024 and July 2025. In July, the first mpox cases were also identified.

In September alone, the WFP reported 270 women and children being diagnosed with moderate to severe acute malnutrition. More than 3,600 children received vitamin A, and 2,000 were dewormed, while 260 women received supplements, and another 870 accessed family-planning services.

The most pressing issue is the lack of money. The UN’s 2025 Humanitarian Response Plan for Mozambique has only received $66 million of the $352 million required, meaning agencies were forced to cut response targets by 70%.

“So far, around 30,000 displaced people have received food, water, shelter, and essential household items,” Paola Emerson, who heads the Mozambique branch of OCHA, told AFP in August. “Funding cuts mean life-saving aid is being scaled back.”

USAID specifically worked to tackle the root causes of conflict and reduce ISIS’ recruitment capability. This involved providing work, food, and shelter, as well as schools for children.

“When those efforts suddenly stopped… it created a vacuum, as well as increased vulnerability and desperation. That vacuum gave insurgents more space to operate, whether through violence or by trying to win over local communities,” the former official told CNN.

Room for Growth in the Energy Sector

Many believed the natural gas reserves could mean the way out of poverty for the country. This, however, has become increasingly difficult as each contractor paused operations.

The Coral South floating LNG project, operated by Italian Eni, started production in 2022; the government currently receives income from the development and is expected to collect $23bn from it over the next 25-30 years.

Another Eni-led project, Coral North, is expected to begin production in 2028, along with US-based oil and gas giant ExxonMobil’s $25bn LNG project that is set to exploit the Rovuma Basin’s reserves.

The government has begun a shift towards renewable energy, utilizing the country’s hydroelectric potential: the Mphanda Nkuwa hydropower project on the Zambezi River will be equipped with a transmission line to the national and regional markets and is expected to double hydro capacity to boost exports and supply sufficient energy to industries.

French energy giant TotalEnergies is set to resume its $20bn onshore LNG project near Cabo Delgado after years-long delays, with Rwandan troops reportedly guarding the site.

However, investors are under increasing scrutiny over human rights violations: most recently, TotalEnergies has found itself charged with complicity in war crimes, torture, and enforced disappearances.

The Mozambiquan army, believing they found a group of insurgents, crammed 200 men into shipping containers at the TotalEnergies gas liquefaction plant, then kept them inside over the next three months. Only 26 survived the beatings, torture, suffocation, and starvation inside.

The gas plant’s construction was stopped in 2021 due to insurgent activity overrunning the region, killing over 1,000 people, including TotalEnergies’ contractors. The Mozambican military was operating out of the facility to protect it against another such attack.

“Companies and their executives are not neutral actors when they operate in conflict zones. If they enable or fuel crimes, they might be complicit and should be held accountable,” said Clara Gonzales, the ECCHR’s co-program director for business and human rights.