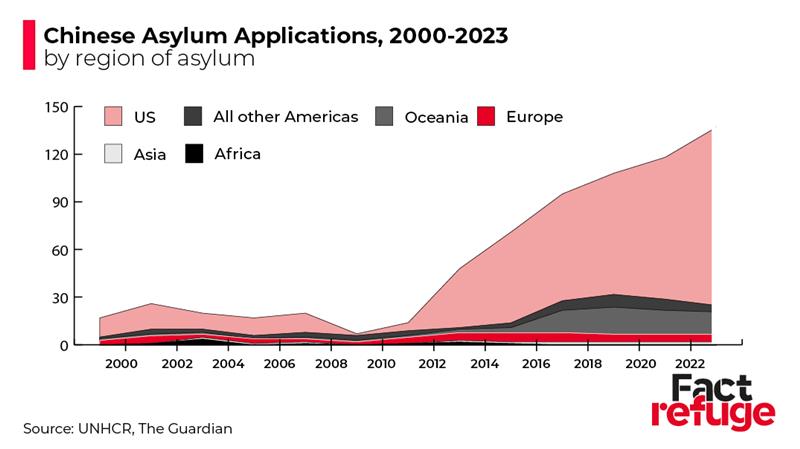

As the Chinese regime becomes ever more authoritarian under the leadership of Xi Jinping, Chinese nationals critical of his policies have come under increasing threat.

Since the restrictive measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, many have opted to leave the county. Some chose to move to surrounding Asian states, resulting in diaspora communities in cities like Bangkok, Tokyo, and Amsterdam.

While most utilize work and study visas to leave, for many, these are not options: due to lack of funds or qualifications, they choose the irregular routes.

There have been two major destinations with two major journeys: one towards the US is the dangerous Darien Gap, and another into the EU through the Balkan corridor. With the closing of the Darien route, even more turn towards the EU and the Balkans.

Reasons to Leave: Unemployment and Surveillance

The regime under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been in control since the end of World War II. Xi Jinping became the General Secretary of the party and thus the country’s president in 2012. Since then, his increasingly hawkish leadership has expanded surveillance, which became especially extensive during the lockdowns implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The lockdowns created a sense that ordinary people who were just living their lives could somehow find themselves under heavy observation of the state or subjected to long arbitrary periods of lockdown and confinement,” says David Stroup, a lecturer of Chinese politics at the University of Manchester. He, like many other experts, argues that the repressive political climate, a worsening economy, and invasive surveillance all contribute to the new trend. Online, the term “runxue” became code for emigrating due to these issues.

Codes are necessary as the government continues to watch its population. Even after leaving, many Chinese migrants are scared to detail their lives, use their names, or seek help from Chinese embassies out of fear that their families back home would suffer the consequences of their ‘betrayal’ of the party.

A migrant, speaking to The Guardian under the pseudonym Zhang, detailed how his situation deteriorated as he voiced criticism of the party’s policies. First, he was arrested in 2012 for questioning the party’s narrative of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea being undisputedly Chinese; at the time, the dispute between China and Japan escalated into Chinese protests.

Rumors spread around his community about his ‘unpatriotic’ behaviour, which led to his wife divorcing him.

During the draconian lockdown measures, he protested but left his phone at home, making his tracking harder for police. Days later his friends were all arrested, leaving him to suspect that losing his phone is what spared him from the same fate.

He says the worsening economic situation contributed to his decision, but it was politics that pushed him to finally leave. Many, however, chose to emigrate due to a stagnating economy and high unemployment.

Ling thought about leaving for more than 20 years, appalled by the education his daughter received, but only endeavored to do so when he lost his job during the pandemic. Mou, an upper-class businessman, saw his business take hit after hit during the pandemic. When he refused to obey a lockdown order, he was detained. His lack of cooperation afterwards led to the police threatening his children’s future education. His family was flying to Serbia, stopping for a transfer in Frankfurt, but instead of boarding their plane, they decided to stay in Germany.

Why the Balkan Route?

As wealthier emigrants can afford legal routes, they tend to emigrate in a similar fashion to Mou. Those with less money and fewer options take the illegal routes; to Europe, the most popular is the Western Balkans, flying into non-EU states with looser rules and crossing illegally into Croatia or Hungary.

Most attempt crossing through Bosnia and Herzegovina, which offers 90-day visa-free stays and shares a long border with Croatia. Serbia is also a popular stopover, offering 30 days visa-free but since recognizing the pattern of migrants utilizing the visa discrepancy with the EU’s policy, it has taken steps to counter it.

Frontex recorded 10 493 illegal crossings between January and October 2025 on the Western Balkan Route. The top five nationalities crossing were Turkish (3184), Syrian (1374), Afghan (1213), Egyptian (954), and Chinese (555). The number of Chinese nationals crossing is already higher than it was for the same period last year, when the spike was first observed, and is expected to rise further.

Speaking to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), Croatia’s Interior Ministry revealed that all Chinese nationals applying for international asylum in Croatia in 2024 (454) and up until September 2025 (377) arrived via Bosnia and Herzegovina “abusing the visa-free regime.”

Numbers are much smaller in the transit states: Bosnia and Herzegovina’s official statistics record only three applicants in 2023 from the total of 21 489. Serbia’s Interior Ministry confirmed its records to be similarly small: only eight in 2023, three in 2024, and five by September 2025.

Bosnia and Hercegovina’s Interior Ministry also recorded a jump in illegal border crossings: from two in 2023 to 151 in 2024.

Despite the number of Chinese migrants increasing, the route itself has seen significant decline with a 78% fall in 2024, and 46% drop in the first ten months of 2025.

Dangers Along the Route

Samir Avdibegović of Vasa Prava – the NGO that recently agreed to provide legal aid to migrants under a new contract with Bosnia’s Security Ministry – told RFE/RL that “We’ve noticed that criminal groups are arriving along with migrants.”

Human trafficking is an especially big problem: an operation between Hungary and Serbia prompted much tension with the EU, forcing Serbia to increase its efforts since 2023. Europol’s Operational Task Force (OTF) also carried out major operations along the Western Balkans, arresting 19 smugglers.

However, many argue that fortifying borders will not stop migrants from arriving.

“Relying solely on enforcement measures to prevent irregular migration could exacerbate the dangers faced by migrants,” writes Dr Annette Idler is the Director of the Global Security Programme at Oxford’s Pembroke College. “Stricter border controls often create unintended consequences, driving desperate individuals to take even more deadly journeys. These measures can also increase the profitability of smuggling, incentivising criminal networks to develop new methods to circumvent restrictions.”