Exactly 40 years ago in 1985, ministers from Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, France, and the Netherlands signed pledges to gradually remove checks on their common borders in the small Luxembourgish commune of Schengen.

The Schengen Area now includes 29 countries: 25 EU Member States and four non-EU countries (Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein). Schengen is the largest cross-country free travel area in the world, and is considered to be one of the main achievements and success stories of the European integration project.

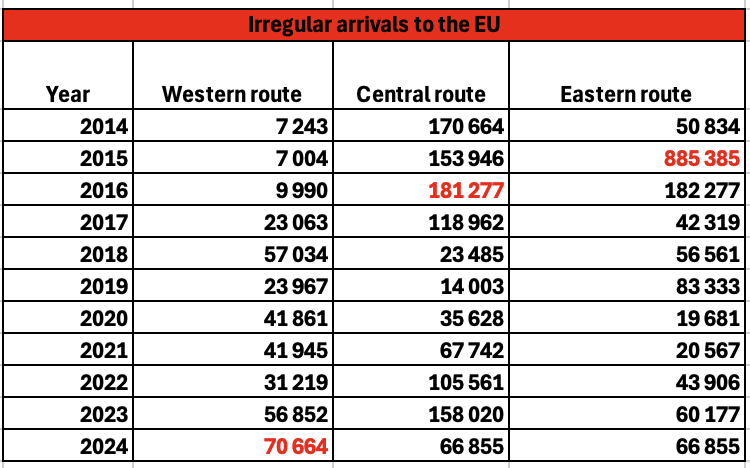

Irregular arrivals into Europe have fallen since 2023. But the political repercussions are already evident: Asylum and irregular migration are unpopular, and far-right parties are rising. Meanwhile, mainstream politicians are attempting to assert control over national borders.

According to the Migration and Asylum in Europe report, in 2023, around 1.3 million non-EU citizens were found to be illegally present in the EU. This is an increase of 13 percent compared with 2022. Among the EU countries, the largest number of illegally present people was found in Germany (264.000).

Central European countries such as Austria, Germany, Poland and Czech Republic account for the greatest use of temporary border controls, of which only Poland has a border with a non-EU country. Besides being destinations in themselves, these countries all serve as transit routes between frequent countries of entry and the riches of Western Europe.

For instance, in October, during the temporary restoration of border controls on the Polish border with Lithuania, over 4,500 people were checked by the Polish border guards. 11 persons were detained, including 3 persons who were refused entry into Poland, and 8 persons were transferred to Lithuania under readmission procedures.

Temporary Border Checks in the Schengen Zone Source: home-affairs.ec.europa.eu

Temporary Border Checks – The Death of Schengen?

“Schengen will continue to evolve, adapt to new realities and respond to the shifting geopolitical landscape,” the EU’s political leadership claims.

According to a newly announced idea, Schengen should adapt to the evolving security landscape with a common intelligence picture, joint operational actions and stronger cooperation among law enforcement authorities, including in internal border regions.

The negative approach of the Commission to the temporary border checks, introduced by some Member States including the abovementioned Germany, as well as Austria and Italy, is quite selfish, as it calls these measure a derogation from the EU’s free-travel principles, regardless the risks and dangers the respective Member States wanted to avoid with border checks, in an attempt to meet their national interests.

Since the ‘refugee crisis’ of September 2015, countries have reintroduced border checks at the EU’s internal borders more than 400 times. These checks have been justified on the grounds of the increased movement of refugees and migrants into Europe, counter-terrorism, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Risks to Undermine the Core of EU

The internal border checks are lawful under amendments made to the Schengen Borders Code (SBC) – the EU’s single set of rules governing border management for the Schengen Area. These amendments – the latest of which was in July 2024 – were aimed at increasing the resilience of the Schengen Area to crises such as public health emergencies, security threats, and the instrumentalization of migrants by third countries.

Exceptional situations, such as terrorist incidents, large-scale organized crime, public health emergencies, or an exceptional situation with sudden large-scale unauthorized movements of non-EU nationals, can be the reasons for reintroducing the checks.

The extension of border checks by EU states risks setting a problematic precedent by undermining the principle of free movement within the Schengen Area. The European Commission and the Schengen Council are responsible for driving such a common approach. But individual countries can also contribute. The success of a common approach requires member states to strengthen their national governance and strategic planning for border controls and to address existing loopholes.